20 weeks, one article a week, and three minutes per article – that’s all you need to get the basics of voice security in place. In Week 2, we talk about Toll Fraud – what it is and how it works.

In my article last week, I mentioned some scary numbers about toll fraud. I’ll make it easy for you – just read the extract here:

- Toll fraud losses in 2021 were over 9 billion dollars, the CFCA found.

- Enterprises lose on average about $40,000 per remote worker exploit[1]

We can go on and on about the kinds of losses that enterprises suffer from toll fraud, but to save time (3-minute read, remember), I’m assuming you’re already aware that toll fraud is a major issue. Three things to note, however – Toll Fraud is a:

- Major hidden issue – significant numbers of organizations are unaware that they suffer from toll fraud, and many have no way to find out how much it affects them. Why? They don’t have the tools. We’ll get into the tools and tech challenge in later reads.

- Revenue problem – it’s leakage of money, rather than theft of data. But certain types of toll fraud are stepping stones for data theft – access to an extension gives access to more information about the enterprise and its ability to control illegal entry.

- The problem for both enterprises and SMEs – if you’ve been breached, you have to pay. This is because of liability issues. When a service provider gives an individual a telephone connection, it is mostly liable for any kind of toll fraud utilizing that number. But when enterprises and SMEs connect PBXes and other infrastructure to the trunks provided by service providers, the bulk of the liability for toll fraud moves over to the SMEs and enterprises.

Defining Toll Fraud

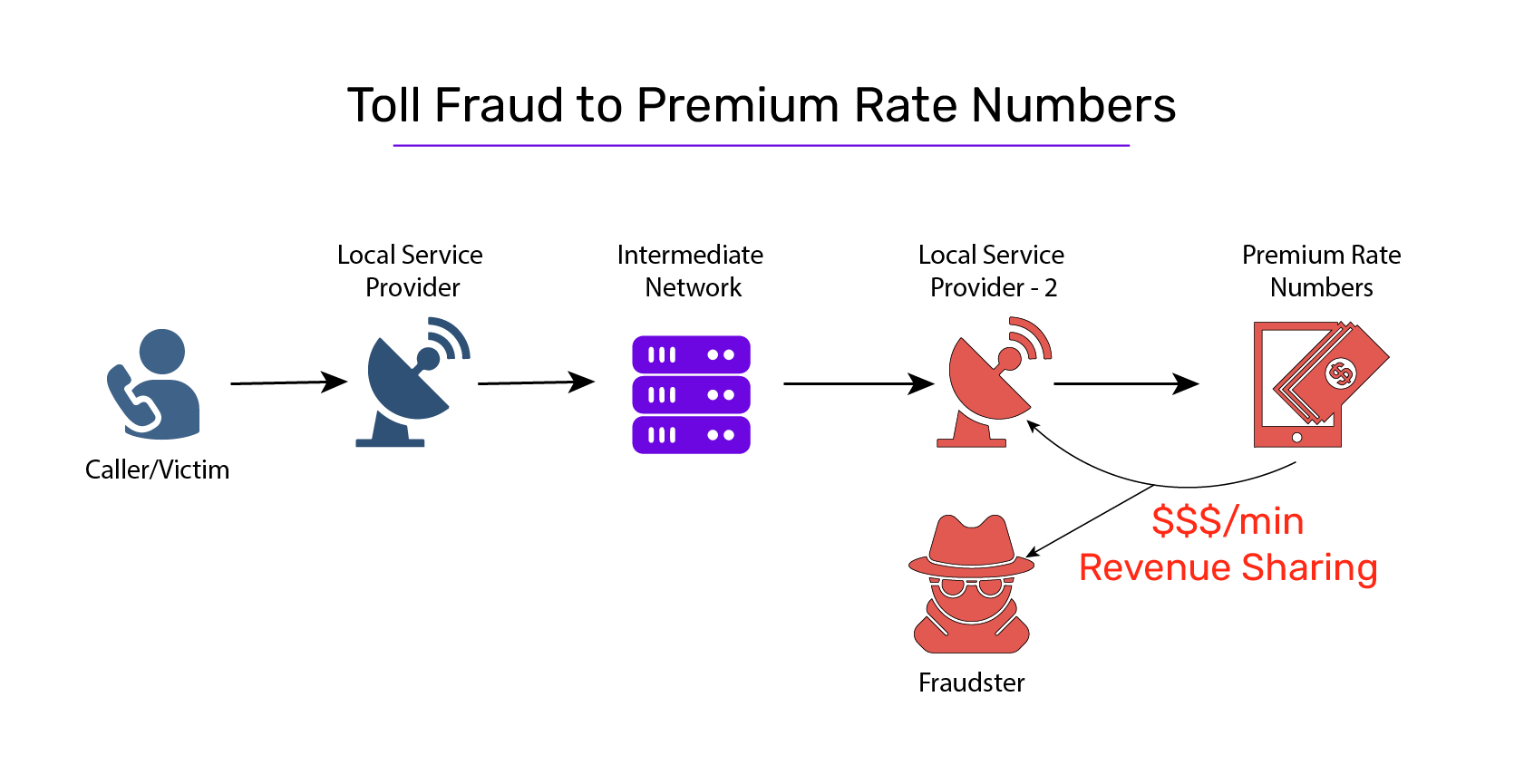

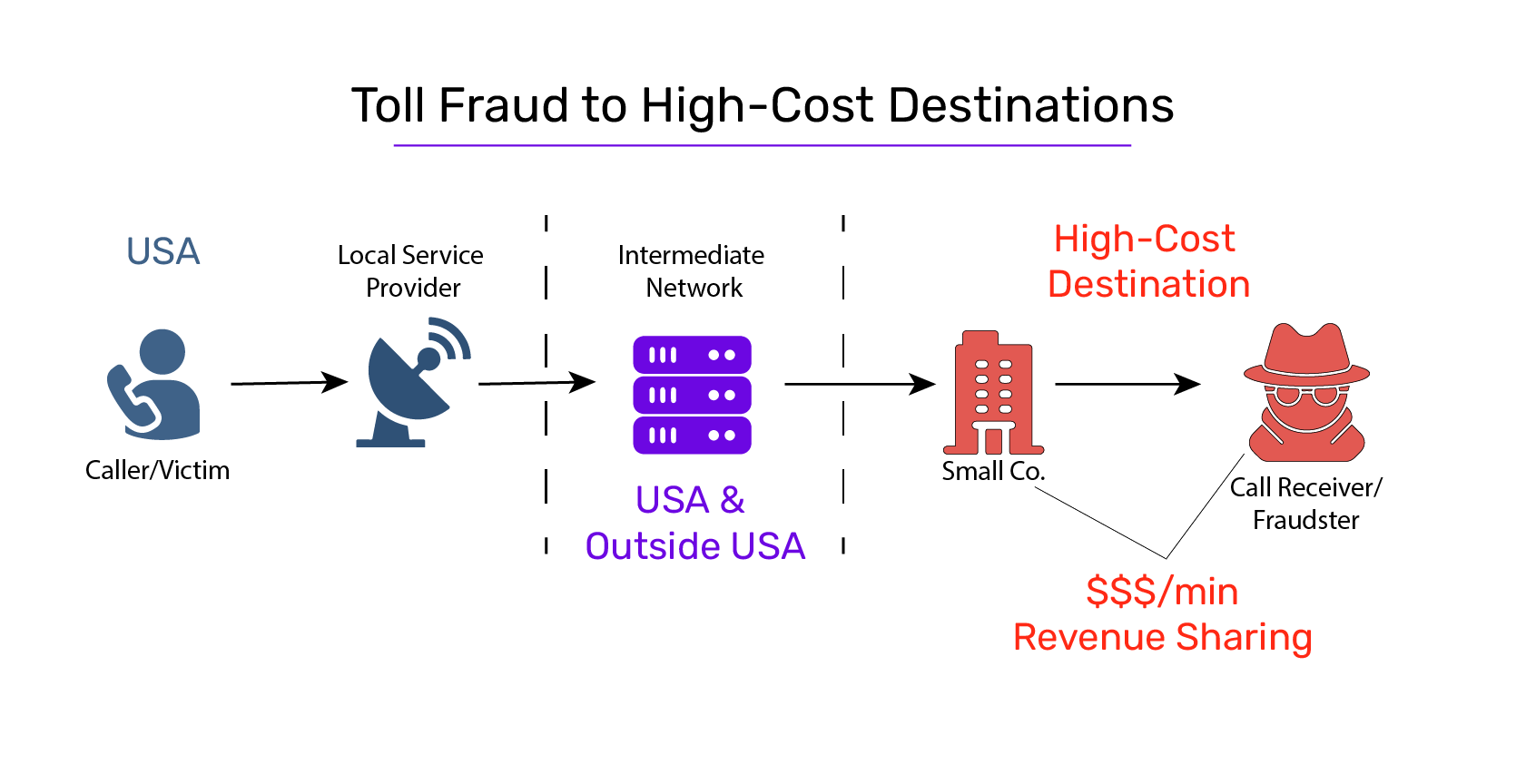

Toll Fraud[2] is the shorthand term used to denote a category of fraud where attackers use your number and call a premium rate number (or a high-cost destination). At the end of the month, when you pay the huge bill, the destination telco pays them a share of the money.

There are all kinds of toll fraud subtypes – Wangiri, Toll-free traffic pumping, etc.; we will talk about them in later articles.

Premium rate numbers: A premium rate number is a special, commercial service, wherein callers pay higher than normal fees for their calls. These are often used by companies that provide specific commercially chargeable services, such as directory lookups, entertainment conversations, and so on.

High-Cost destinations: Certain nations (for example, Caracas, Lithuania, Cuba, Lesotho, and so on) charge incoming international calls at very high rates. This is a bit of a subjective issue – what exactly is high cost, but subjectively, a high-cost destination is one that gives you billing shock.

The Game Plan

Assume Joe Fraudster, as part of his diversification from regular low-level cheque fraud and so on, has decided to go upmarket. Toll Fraud is a good idea to explore.

- Joe connects to a small service provider (Smallco) in Cuba, Lithuania, Lesotho, or one of another few dozen countries.

- He tells them he wants Premium Rate Numbers (PRNs) and is willing to guarantee a ton of traffic terminating to these PRNs, provided Smallco shares a percentage of the billings with him.

- Smallco salesperson is thrilled to have met Joe – his golden ticket! The rate for calling into these PRNs is set at USD 1 per minute.

Now it’s time to unleash the attack. Welcome, Joe Fraudster, back to the USA!

The Toll Fraud Attack

When a new device goes on the internet, crawlers released by Joe Fraudster begin probes within minutes.

- When a crawler identifies that the device is an SBC, a series of additional probes are automatically launched, usually culminating in an extension enumeration attack – an attempt to figure out the dialing ranges available on the communication network fronted by the SBC. If successful, the attacker gets hold of the range of extension numbers.

- Usually, extensions have a 4 or 6-letter password, and very often it’s just numbers. That’s the kind of stuff that attackers love – short passwords, with little ‘noise’. Their automated tools easily and quickly brute-force through the extensions – a spray of commonly used passwords is usually enough to find their way in.

- Once attackers find their way into an extension, a new automation tool takes over – testing the permissions of the extension – is it allowed to make international calls? Which locations are permitted, and which are not? Is it allowed to connect to high-toll destinations?

- At this point, Joe Fraudster has a choice to make –

- A Big Squeeze: An attacker in a hurry will make a boatload of calls to a high-cost number as quickly as possible – the idea is to extract as much value as they can before they are found out – usually because the service provider notices the spike and notifies the victim company. After a ton of calls (maybe over a weekend), Joe Fraudster is locked out and starts looking for new victims.

- Slow and Steady: Smarter, more mature attackers have conquered their urge to hurry – instead, they make a few phone calls per day from the compromised extensions, at times when the company is active. They avoid the obvious triggers – calls on weekends, calls on holidays, and so on… slowly bleeding the company for months, even years. If needed, they steadily increase the billings over many months, so that the company sees an increase in billing over a long time, instead of a spike – making the whole thing explainable – mergers took place, changes in billing plans, etc. No one looks and Joe Fraudster gets a steady source of income.

Toll Fraud has many attack vectors, and the above description is a simple approach.

Another example (a modified-Wangiri attack) that we recently saw in the field went like this:

- Attackers found a company that allowed automatic callback through its IVR if a customer requested that it get back in touch.

- They placed calls from a PRN based in a South African country to the IVR and requested a callback.

- When the callback took place, it was to the PRN, billed at approximately USD 3.5 per minute.

When we were called in and analyzed the company’s phone records, we realized they had paid out over USD 200,000 in excess fees over the last 3 months.

In the next article, we shall look at some of the challenges companies face to identify toll fraud, some tell-tale signs, and some techniques to prevent it or fight it.

If you have any questions, please let us know at: SecurityEducation@assertion.cloud.

[1]Data Breach Costs Increase by $1 Million When Remote Workers Are Involved (knowbe4.com)

[2] The formal name is International Revenue Share Fraud (IRSF)